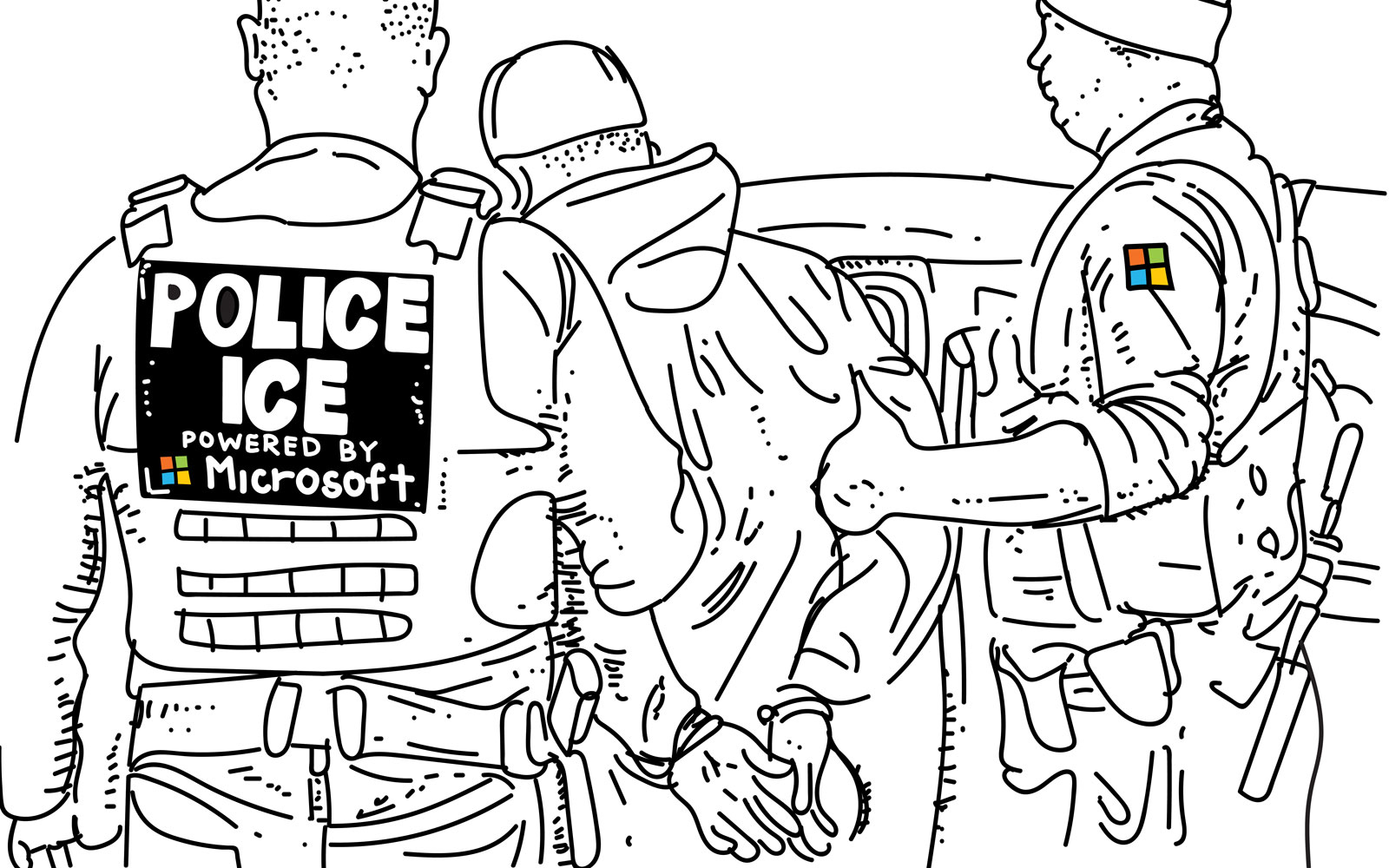

Nearly a decade ago, I had the good fortune of being one of the last people to interview the founder of Commodore International, Jack Tramiel (famous for Commodore computers and the popular C64), before he passed away. At 83 he died from heart failure after pioneering the consumer market for personal computers and home gaming, and working toward changing people's lives for the better through technology. What few people knew, and what I discovered in our interview, was that the foundational concept driving the Commodore 64 was Tramiel's vision for a future in which the Holocaust and its concentration camps (from which Jack survived but his father did not) would never be able to happen again. In our interview Mr. Tramiel told me: I made the market for the computer youth-driven. I went around the world meeting young people in computer clubs and showing them what the computer can do. And I concentrated on a special country which is called Germany. Because I am a Holocaust survivor. And because of that I wanted to make sure that the German youth will learn from the computer what the Holocaust was all about. And we had a piece of software which did that. At the same event I also interviewed Bill Lowe, father of IBM PC. While Jack Tramiel was rounded up at the age of 11 and shipped with his parents to Auschwitz in 1944, IBM and its subsidiaries helped create enabling technologies for the Third Reich; from identification of Jews in censuses, registrations, and ancestral tracing programs, to the running of railroads and organizing of concentration camp slave labor. IBM founder Thomas Watson's custom-designed complex data solutions are how Hitler got everyone's names, identities, and locations for his brownshirts to round up, put in work camps, torture, and murder. You have to wonder what kind of people worked for IBM during this time. It's possible to suggest that they weren't completely aware of what they were really part of. Especially considering IBM's structured denials and, as the New York Times self-describes as its "staggering, staining failure [of The New York Times] to depict Hitler's methodical extermination of the Jews of Europe as a horror beyond all other horrors." (The reporting was there, but it was couched in softened language, ran against the paper's incorrect opinion that Hitler couldn't really be a racist, and buried deep behind culture features about Hitler and his positive polling numbers.) More than asking what kind of people would work in a tech capacity to provide technical solutions for genocide, it's interesting to wonder how they felt about it. Was the suffering of others an abstract, or were they more like former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, mocking and pointedly indifferent? Perhaps they felt like Microsoft employees, some of whom this week repudiated the company between news of the US government's human rights violations in regard to immigrants and asylum-seekers, and Microsoft's role in providing tech solutions for ICE (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement). In response, the company publicly backpedaled. CEO Satya Nadella published an internal employee memo on LinkedIn stating that Microsoft is "not working with the US government on any projects related to separating children from their families." Yet it's hard to know how that's even possible considering what Microsoft itself has described about the relationship. In a January blog post, Microsoft explained that it was excited to advance the capabilities of ICE with its Azure product: to "help employees make more informed decisions faster, with Azure Government enabling them to process data on edge devices or utilize deep learning capabilities to accelerate facial recognition and identification."

Microsoft's post came only a few weeks after nationwide roundups of immigrants by ICE, under the direction of the Trump administration, had increased, hitting headlines (yet again) when ICE's director promised punishment on the state of California for trying to protect people from raids. As in, being identified, tracked down, dragged from their homes and workplaces, and incarcerated in camps and jail cells. But we knew all this, and Microsoft employees aren't the only tech workers starting to feel uncomfortable about being part of what's increasingly starting to look like IBM 2.0, as it were. On one end of the spectrum we have people eager to innovate the new regime's abilities to hunt and cage human beings, like disgraced Oculus Rift founder Palmer Luckey's Anduril Industries and its "virtual wall." Facebook also swims at this end of the pool, with its rules safeguarding Holocaust denial and its role in genocide in Myanmar. (I often wonder what Jack Tramiel would've thought about Facebook's staunch stance to perpetuate Holocaust denial. We will forever wonder how much one decade of that policy shaped what we've become, a nation now known for "tender age" toddler camps.) On the other end are Google's employees, whose Project Maven work of artificial intelligence analysis of drone footage for the Defense Department caused internal backlash so bad they dropped the contract. "Thousands of employees have signed a petition asking Google to cancel its contract for the project," Gizmodo reported, "and dozens of employees have resigned in protest." Somewhere in the middle are 2,843 tech workers who signed a neveragain.tech pledge during the brief time when the petition was open. In December 2016, just before Trump was sworn into office (and his week-later travel ban, aka "Muslim ban" went into effect), it was signed by 53 Microsoft employees, 138 Google employees, 15 from Amazon, six from IBM, and four from Facebook (among other companies). Not surprisingly, as baby prisons and ghastly child abuse factories have come to light the hashtag #neveragaintech has resurfaced on Twitter as techies experience another round of uncomfortable contact with the outside world — and their indisputable roles in America's head-on human rights catastrophe. Maybe people working for companies that innovate ICE and protect Holocaust erasure are as David Roth wrote for Deadspin, possessing of "a worldview that allows for unimaginable suffering and injustice precisely because it refuses even to imagine that suffering and injustice or the people broken under it." Were the people at IBM streamlining Nazi genocide just callously indifferent techie hipsters of another era? Or, maybe the techies who abide by Holocaust denial policies or try to make it seem like their company is only providing "legacy" services to ICE and its concentration camps — they just can't believe any of this is really happening. I mean, since not everyone can be as gleefully, monstrously cruel as Palmer Luckey or Corey Lewandowski, it's got to be one or the other, right? Earlier this week I went for a run that took me through one of San Francisco's beautiful parks. As I began to pass its dog run area, there was a horrible dog attack in which a pit bull tore into and then locked on to a dog, with its owner's hand trapped in the middle. I physically helped the injured dog, and then her injured guardian, and somehow people handed direction of the scene to me, including dialing 911 and shoving a phone in my bloody my hand. It was awful. I'll never get those screams out of my head. I'm still finding blood on my clothing. The big thing that struck me in the aftermath was how completely unfocused and directionless everyone became during the most critical parts of breaking up the attack and getting the injured to safety. Just standing there during the screaming, the howling, needing someone (anyone!) to tell them what comes next, how to help. Overwhelmed by the terribleness. Like they couldn't believe it was really happening. I get it. I really do. Yet when your hands are covered in blood, the time to stand around stuttering in disbelief hoping someone else will do something has long passed. Images: NurPhoto via Getty Images

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2tmfDHx |

Comments

Post a Comment