By Kevin Purdy This post was done in partnership with Wirecutter. When readers choose to buy Wirecutter's independently chosen editorial picks, Wirecutter and Engadget may earn affiliate commission. Read the full blog here. We set out to do a standard Wirecutter guide to the best antivirus app, so we spent months researching products, reading reports from independent testing labs and institutions, and consulting experts on safe computing. And after all that, we learned that most people should neither pay for a traditional antivirus suite, such as McAfee, Norton, or Kaspersky, nor use free programs like Avira, Avast, or AVG. The "best antivirus" for most people to buy, it turns out, is not a traditional antivirus package. Information security experts told us that the built-in Windows Defender is good-enough antivirus for most Windows PC owners, and that both Mac and Windows users should consider using Malwarebytes Premium, an anti-malware program that augments both operating systems' built-in protections. These options provide reliable protection without slowing your computer significantly, installing unwanted add-ons, or harassing you about upgrades. Malwarebytes is not an all-in-one option for protecting your system against exploits, malware, and other bad stuff. But information security experts repeatedly recommended it as a useful anti-malware layer, one of multiple layers of security you need for your devices, coupled with good habits. Relying on any one app to protect your system, data, and privacy is a bad bet, especially when almost every security app—including Malwarebytes and Windows Defender—has proven vulnerable on occasion. You should have good virus and malware protection, yes, but you also need secure passwords, two-factor logins, data encryption, and smart privacy tools added to your browser. Check out our guide to setting up those layers here. Why you should trust us As writers and editors for Wirecutter, we have combined decades of experience with different computers and mobile devices, and their inherent vulnerabilities. We spent dozens of hours for this guide reading results from independent labs like AV-Test and AV-Comparatives, features at many publications such as Ars Technica and PCMag, and white papers and releases by institutions and groups like Usenix, Google's Project Zero, and IEEE. We also read up on the viruses, ransomware, spyware, and other malware of recent years to learn what threats try to get onto most people's computers today. Then we interviewed experts, including computer-security journalists, experienced security researchers, and the information security team at The New York Times (parent company of Wirecutter), whose responsibilities include (but are not limited to) protecting reporters and bureaus both overseas and here in the US from hacking and surveillance: - Brian Krebs, journalist and operator of Krebs on Security

- Bill McKinley, executive director of information security for The New York Times (parent company of Wirecutter), and others on The Times's information security team: Neena Kapur, James Pettit, Runa Sandvik, and David Templeton

- Rich Mogull, CEO and analyst at independent security research firm Securosis

- Joseph Cox, writer on computer security and crime for Motherboard

- Whitson Gordon, former editor of Lifehacker and How-To Geek

- Alan Henry, editor of the Smarter Living section of The New York Times, and former editor of Lifehacker.

These experts helped us reach a more nuanced consensus than the typical table-tennis headlines: antivirus is increasingly useless, actually it's still pretty handy, antivirus is unnecessary, wait no it isn't, and so on. Although we often test all the products we're considering, we can't test the performance of antivirus suites any better than the experts at independent test labs already do, so we relied on their expertise. Furthermore, every information security expert we talked to agreed that most people shouldn't pay for a traditional antivirus suite: The virus and malware protection built into Windows and macOS, combined with good habits, are enough for most people. Malwarebytes is a nonintrusive additional layer, one that may catch things written to work around Windows Defender or the Mac's inherent defenses. So we tested Malwarebytes on Windows and macOS to learn how easy the app was to use, if it noticeably slowed performance or interfered with other apps, or if it had any annoying notifications. Why we don't recommend a traditional antivirus suite It's insufficient for a security app to just protect against a single set of known "viruses." There are potentially infinite malware variations that have been crypted—encoded to look like regular, trusted programs—and that deliver their system-breaking goods once opened. Although antivirus firms constantly update their detection systems to outwit crypting services, they'll never be able to keep up with malware makers intent on getting through. [pullquote]Although each expert we interviewed had their own preferred solutions to the endless stream of computer threats, none recommended buying a traditional antivirus app.[/pullquote] A quick terminology primer: The word malware just means "bad software" and encompasses anything that runs on your computer with unintended and usually harmful consequences. In contrast, antivirus is an out-of-date term that software makers still use because viruses, Trojan horses, and worms were huge, attention-getting threats in the 1990s and early 2000s. Technically, all viruses are a kind of malware, but not all malware is a virus. Although each expert we interviewed had their own preferred solutions to the endless stream of computer threats, none recommended buying a traditional antivirus app. So why shouldn't you install a full antivirus suite from a known brand, just to be on the safe side? For many good reasons: - Vulnerabilities: The nature of how antivirus apps provide protection is a problem. As detailed at TechRepublic, "Security software necessarily requires high access privileges to operate effectively, though when it is itself insecure or otherwise malfunctioning, it becomes a much higher liability due to the extent to which it has control over the system." Symantec and Norton, Kaspersky, and most other major antivirus vendors have all had critical vulnerabilities in the past.

- Performance: Antivirus software is notorious for slowing down computers, blocking the best security features of other apps (such as the Firefox and Chrome browsers), popping up with distracting reminders and upsells for subscriptions or updates, and installing potentially insecure add-ons such as browser extensions without clearly asking for permission.

- Privacy: Free antivirus software has all of the above problems plus added privacy concerns. Good security is not free, and free-to-download apps are more likely to collect data about your computer and how you use it, as well as to install browser extensions that hijack your search and break your security and add an advertisement to your email signature.

For these reasons, we don't recommend most people spend the time or the money to add traditional antivirus software to their personal computer. We didn't consider newer antivirus products that have not yet been tested by known independent research labs or that aren't available to individuals. Two caveats to our recommendations on malware protection: - If you have a laptop provided by your work, school, or another organization, and it has antivirus or other security tools installed, do not uninstall them. Organizations have systemwide security needs and threat models that differ from those of personal computers, and they have to account for varying levels of technical aptitude and safe habits among their staff. Do not make your IT department's hard job even more difficult.

- People with sensitive data to protect (medical, financial, or otherwise), or with browsing habits that take them into riskier parts of the Internet, have unique threats to consider. Our security and habit recommendations are still a good starting point, but such situations may call for more intense measures than we cover here.

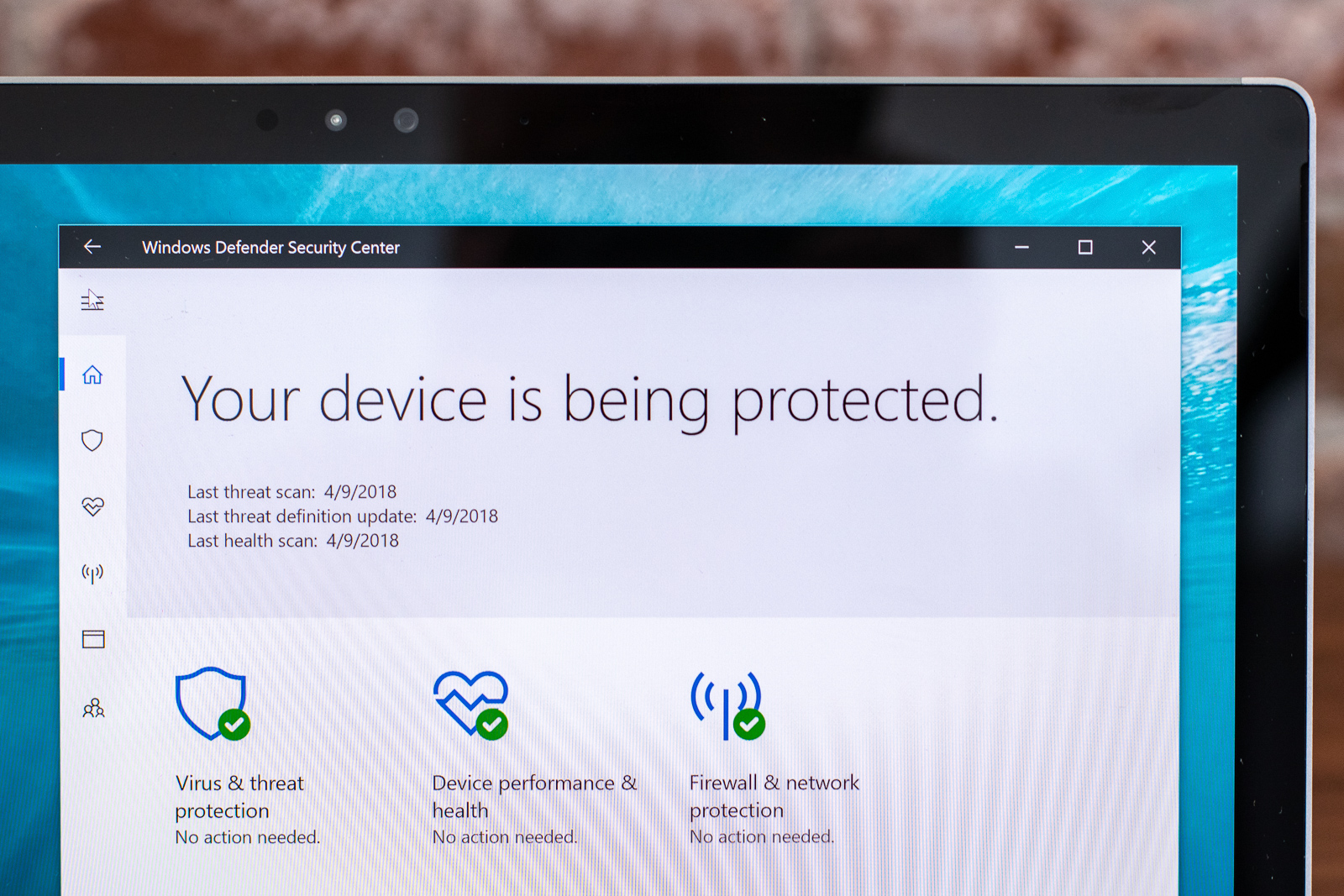

Windows Defender is mostly good enough

Photo: Kyle Fitzgerald If you use Windows 10, you already have a robust antivirus and anti-malware app—Windows Defender—installed and enabled by default. The AV-Test Institute's independent testing gave Windows Defender the best possible rating in protection in December 2017, and a nearly perfect rating in performance. All the experts we spoke to recommended that most people stick to Defender as their antivirus app on Windows. "Defender, coupled with Malwarebytes (real time protection) is good 'enough' for most," said Bill McKinley of The New York Times (parent company of Wirecutter). Windows Defender is "good enough," said Whitson Gordon, and James Pettit of The Times said his recommendation was to "turn on Windows Defender (and) call it a day on the antivirus front." Alan Henry told us that Defender was "good again after a period of sucking really bad," and so "probably enough, combined with good internet habits." Because Defender is a default app for Windows 10, by the same company that makes the operating system, it doesn't have to upsell you or nag about subscriptions, and it doesn't need the same kind of certificate trickery to provide deeply rooted protection for your system. It doesn't install browser extensions or plug-ins for other apps without asking. Windows Defender does have the problem of being the default detection app that malware makers first attempt to work around. But having layers of security and good habits—especially sticking to official app stores and not downloading questionable free versions of things you should pay for, as we cover in another guide—should keep you safe from the worst kind of Defender-defeating malware. AV-Test dinged Defender in usability in December 2017 due to false detections of legitimate software—it wrongly detected 16 out of 1.3 million. But that's a very small number. False detections, although annoying when too common, are preferable to a failure to catch something malicious. And although AV-Test gave Defender a demerit for slowing down the installation of some apps, the Microsoft app earned top marks and beat industry averages for launching websites, starting apps, and copying files, tasks you do far more often than installing apps. And when a major vulnerability was discovered in Defender in May 2017, the fix was remarkably fast—from a Friday-night disclosure to a Monday-evening patch. Why Macs don't need traditional antivirus Due to a combination of demographics, historical precedent, and tighter controls, Macs have long been less vulnerable to infection than Windows computers: - People have far fewer Macs than Windows computers: Over the past year, 12 percent of Web-browsing desktop computers ran macOS, compared with about 82 percent for all Windows versions combined, so macOS is a less lucrative target for parties making malware.

- Macs include a wider variety of useful first-party apps by default, and both macOS and downloaded apps receive updates through Apple's own App Store. Windows PC owners are more accustomed to downloading both software and hardware drivers from the Internet, as well as providing permissions to third-party apps, which are more likely to be malicious.

- Newer versions of Windows must make concessions to allow apps made for older versions of Windows to run, creating a complicated set of legacy systems to secure. In contrast, macOS has seen less change since the introduction of OS X, and Apple has been less hesitant to render apps made for older versions obsolete.

This is not to say Macs lack any vulnerabilities. Mac owners who install a bad browser extension are just as vulnerable as Windows or Linux users. The Flashback malware exploited a Java vulnerability and tricked more than 500,000 Mac users in 2012, or about 2 percent of all Macs. More than anything, though, relying on any one aspect of your system, even the inherent protections of a Mac system, is foolish. That's why we recommend adding one extra tool to your Mac to guard against a broad variety of security threats. Why we recommend Malwarebytes Premium for both Windows and macOS

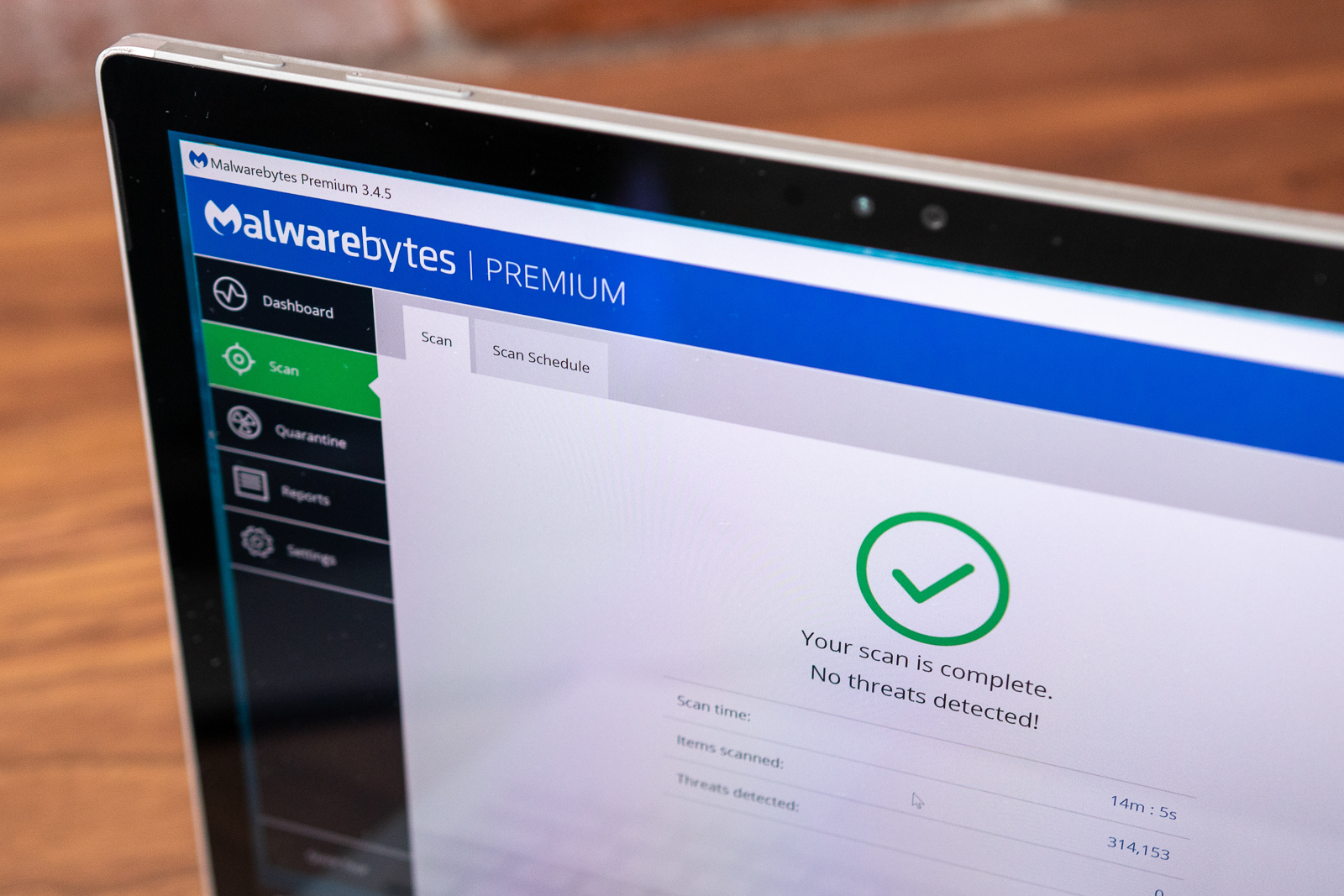

Photo: Kyle Fitzgerald All the experts we spoke to recommended that Windows users run Defender, but also said it worked best when paired with Malwarebytes Premium. Like Windows Defender, Malwarebytes almost never gets in your way or bugs you for more money, and it's a dead-simple app that doesn't require tweaks to a bunch of settings. With the two apps, there is some overlap in coverage, but Windows Defender and Malwarebytes can run alongside each other peacefully. While Windows Defender serves as a traditional system-protecting antivirus layer, Malwarebytes Premium protects you from newer threats not traditionally spread by email, USB drives, or other old-fashioned avenues. Malwarebytes looks for any program doing the kinds of things that malware does, not just a known list of bad actors. (This difference in approach is partly why Malwarebytes is not included in institutes' and publications' antivirus-software tests, which often rely on running a list of known threats against each software suite.) Malwarebytes also looks for junkware installed alongside other apps, potentially unwanted programs (PUP), and exploits present in applications already installed on a system, as explained in a Malwarebytes blog post: Antivirus usually deals with the older, more established threats, such as Trojans, viruses, and worms. Anti-malware, by contrast, typically focuses on newer stuff, such as polymorphic malware and malware delivered by zero-day exploits. Antivirus protects users from lingering, predictable-yet-still-dangerous malware. Anti-malware protects users from the latest, currently in the wild, and even more dangerous threats. David Templeton of The New York Times (parent company of Wirecutter) told us that, two years ago, he wouldn't have suggested Macs needed malware protection. But the rise of browser vulnerabilities and adware installed alongside legitimate apps (usually those downloaded from outside Apple's App Store) makes Malwarebytes a good idea at a reasonable price. Malwarebytes offers a free trial of its Premium version for Windows and Mac (14 days and 30 days, respectively). The Windows and Mac apps are all but identical: Both live in the system tray, work in the background, and have an uncomplicated dashboard you can mostly ignore. After the trial, Malwarebytes costs $40 per year, or a little over $3 per month. We recommend the Premium version because, unlike the free version, it performs real-time scanning—if you leave to yourself the task of manually scanning for things already on your computer, that's no kind of security. But the best protection is layers and good habits Everyone we spoke to said that while virus and malware protection was necessary, the idea that any one app could be universally aware of and protect against all threats was ludicrous. As security journalist Brian Krebs writes, "[Antivirus] is probably the most overstated tool in any security toolbox." We've written a guide to the best layers of security and good habits for anyone who uses a computer. This blog may have been updated by Wirecutter. To see the current content, please go here. When readers choose to buy Wirecutter's independently chosen editorial picks, Wirecutter and Engadget may earn affiliate commissions.

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2Iml8MA |

Comments

Post a Comment