There are many ways to buy a video game. You can snag a physical copy, peruse a digital store like Steam, or subscribe to massive Netflix-style services such as PlayStation Now and Xbox Games Pass. There's no shortage of options, but that hasn't stopped Sokpop -- an indie 'collective' in the Netherlands -- from trying something different. For $3 per month, you can access a new game made by the team every fortnight. That's right. Every. Fortnight. In addition, the team is working on larger projects that will, once they're complete, be accessible to subscribers too. Sokpop's experimental releases include Llama Villa. You begin the quirky title with a rickety pen and enough cash to buy the bare essentials: a bucket of water, some straw, sprinklers and a plant for the llama to pee on. It all seems rather tame until you click on the creature and realize you can sheer its silky coat for money. Suddenly, you have the funds to build a house with walls, doors and carpet. Keep your llama fed and you can trim it once more, netting enough cash for another animal or, if you prefer, a TV. Within the first hour, you'll have a mansion brimming with llamas who magically know how to brew coffee, take relaxing showers and browse the internet using ultra-thin laptops. It's bizarre and utterly incredible.

Llama Villa is The Sims, but with llamas. All of Sokpop's games share this joyously weird vibe. Botanik, for instance, is a gardening simulator with seeds that can walk about and worms that you need to pick up and fling away from your precious plants. Hoppa, meanwhile, is about a bumbling explorer who can plant his walking stick and leap between lily pads like an infant pole-vaulter. My personal favorite, though, is Simmiland, a civilisation builder based around a small deck of cards. Your god-like actions are limited by the hand you draw, and once your deck is depleted everyone is wiped out by the apocalypse. Sokpop titles are only available on Windows and macOS. Members subscribe through Patreon and redeem their games through a special key that links to the indie storefront Itch. Every subscriber also has access to a Discord channel where they can discuss the latest Sokpop releases. The collective consists of four friends: Aran Koning, Tijmen Tio, Tom van den Boogaart and Ruben "Rubna" Naus. They met through university and community events including the long-running Ludum Dare game jam. One day, in Berlin, the group got "really drunk together" and talked about "how it would be really cool to become a boy band," according to Tio. Instead of a traditional studio, the group wanted to work on their own projects, but under a collective banner that would give everyone greater exposure. Botanik is a tamagotchi-inspired gardening game with plants, seeds and worms. At the end of 2015, the team formalized Sokpop by creating a Twitter account. "That was the first official thing we did," Koning recalls. "Let's make a Twitter account, say we're a group of people, and post lots of GIFs!" None of them were sure if Sokpop could actually make money, however. Some thought games would always be their hobby, or side project, while they worked for larger companies. Once all four members had graduated from university, however, everyone started taking the project more seriously. "We had a big conversation about it," Tio said. "Like, 'no, we can totally pull this off.'" New patrons only gain access to the last two games that Sokpop has produced. Sokpop launched its Patreon at the end of 2017. The group chose its unusual subscription model because it wanted to keep making smaller, inventive games that wouldn't work as larger titles or attract the necessary funding through Kickstarter and traditional publishers. The four friends had built a small, but highly supportive following on Twitter, too, by meeting people on various trips and uploading a steady stream of cute and comical animated GIFs. Instead of reaching for a larger audience, the collective realized it would be better to serve this niche but highly engaged group of fans first. At the time of writing, Sokpop has made 19 games for 687 patrons chipping in $2,556 every month. The collective also sells each of their titles separately through Itch for $3. The dual-distribution is necessary because new Patrons only gain access to the last two games that Sokpop has produced, as well as every title released thereafter. The group compares this to a magazine subscription; if you sign up for Vogue or Vanity Fair, the publisher doesn't mail you every back issue. It wouldn't be fair, after all, to the people who have supported the project since day one. The Itch store also caters to people who only want to play a couple of Sokpop's wares.

Simmiland is a devilishly hard civilisation game. The subscription model ensures that the team gets a regular and mostly reliable source of revenue every month. Kickstarter, by comparison, gives developers a large lump sum that they then have to manage until the game's release. It's a stressful cycle or pitching, building and praying for sales. Sokpop's system is closer to a wage and reduces the commercial and creative risk associated with each game. You're buying into the team and its expanding library of experiments, rather than one particular project. "A lot of people realize that it's pretty cheap, and that if it's not a game they like, they'll get a new one in two weeks," Koning said. "If it's not a game they like, they'll get a new one in two weeks." The Patreon and Itch revenue isn't enough for the team to survive, however. All of them balance Sokpop with freelance work that helps pay for food and rent. That puts pressure on the collective and its ability to release games every two weeks. At the moment, the four Sokpop members work almost exclusively on their own. They're each responsible for one title every two months, which usually requires a week of prototyping, a fortnight of serious development, and a final week of polish, bug-fixing and promotion. That leaves another month for freelance work, vacation, and the larger, long-term games promised to patrons. A month isn't long to fine-tune a video game. Sokpop, though, was used to making game jam projects in roughly 48 hours. Four weeks, by comparison, felt like plenty of time to craft something short and experimental. "What we forgot, or didn't quite realize, is that we really don't want to spend 40 hours of a 48-hour weekend making a game," Koning said. The first few titles were chaotic to produce, but slowly Sokpop has found its rhythm. The team has got better at 'scoping' -- knowing how large a project should be -- and structuring their workflow. Spider Ponds is about spinning webs and catching prey in the forest. Sokpop has worked together on a few games, including Lassos for the indie game festival Fantastic Arcade. Most of the time, though, the group's tight deadlines and deeply personal ideas make it difficult for the different members to collaborate. "We've thought about it a lot," Koning hinted. To keep the business on track, the collective works in a shared office space and holds a catch-up meeting every Monday. "We call it a meeting and we try to be really professional about it, but in reality it's just us sitting on camping stools outside in the sun," Tio said. "Or on the ground. And half the time we're just making jokes." Sometimes a team member will fall behind and ask for an extra week to complete a game. But for the most part, Sokpop has kept its promise and delivered every fortnight. The collective's Patreon is a fascinating idea. Most Kickstarter campaigns are built around a product, or service, that backers would like to own or see come to fruition someday. Patreon pages, meanwhile, are about supporting a person, or group. Sokpop's model is a strange mixture of both: the group's patrons want the fortnightly games, but they're also aware and invested in the people behind them. For all four members, then, building their personal and collective brands online, similar to a YouTube or Twitch star, is just as important as the games they're putting out every month.

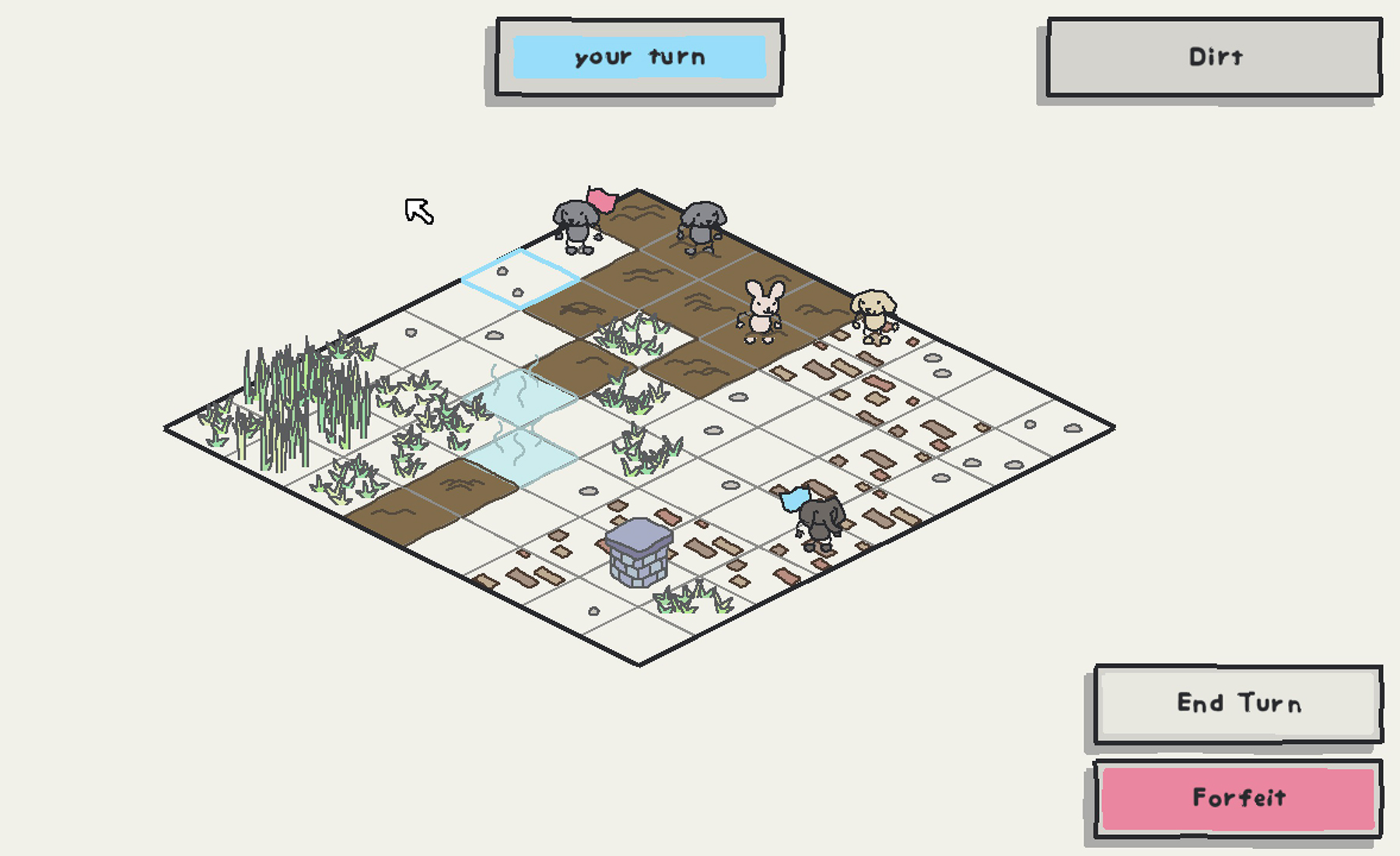

Zoo Packs is a grid-based strategy game with cute animals. Tio and Koning say this shift is emblematic of the wider entertainment industry. People aren't just interested in the latest Childish Gambino album -- they want to know everything about Donald Glover, including his personality, opinions, and the various TV and movie projects that he's working on. Video game development is evolving in a similar way. Many are curious about the lives of their favorite indie developers, as well as established figures such as Hideo Kojima, Cliff Blezinski and Markus 'Notch' Persson. Supporters track them on Twitter and Instagram -- wherever they post, essentially -- admiring their selfies and art equally. Sokpop's long-term success hinges in part on a similar level of fan engagement. If the group can build a larger following, it will attract more patrons and, eventually, the funding required to ditch their freelance work. That, in turn, would prove that a subscription model is possible for at least some developers who work with a similar style, pace and quality. Source: Sokpop (Patreon)

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2DvCJDl |

Comments

Post a Comment