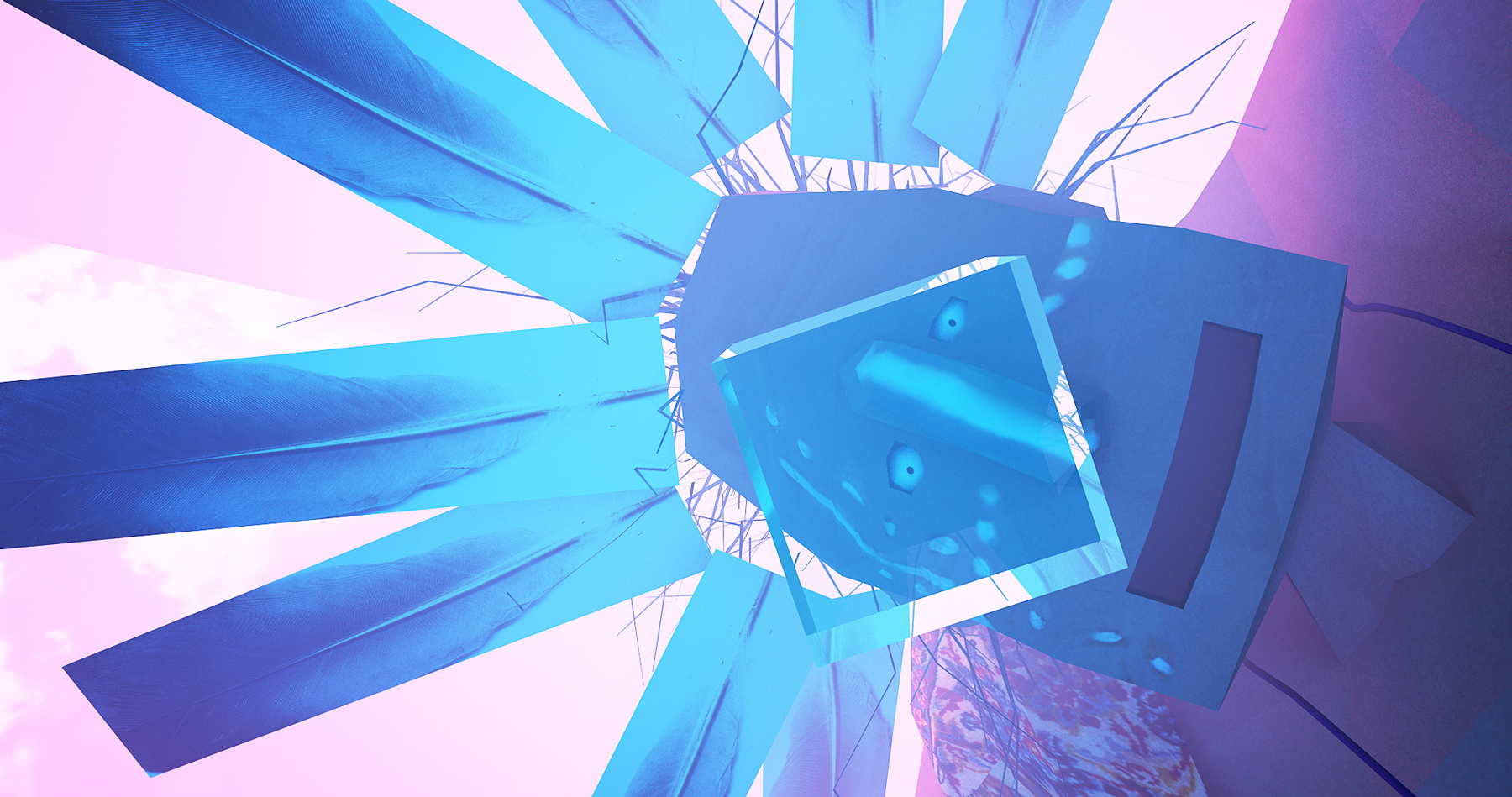

Ugly is a film built on beautiful contradictions. The characters have odd, blocky proportions and stumble around like a group of drunk boxers. The town, too, is comprised of weirdly angular cars, buildings, bicycles and trash bags. There's a consistency to the art style, though, that resembles origami and the papercraft video game Tearaway. And the lighting, a stunning mixture of pastel pinks and blues, gives every frame a warm, inviting sheen. It's an unusual, attention-grabbing blend that feels both charming and unsettling at the same time. The aesthetic mirrors the story, which follows a wild tomcat, Ugly, and its friendship with a Native American chief called Redbear Easterman. At first, the world seems like a bleak place full of hurtful humans who want to bully the one-eyed creature. In one scene, for instance, a group of firefighters spray Ugly with a hose while a building burns to the ground behind them. Redbear sees the value in all life, though, and helps Ugly dream of a flourishing forest filled with creatures that float serenely through the air. The film's exploration of appearance and kindness goes deeper than the story and character models, though. The team behind Ugly built the short using an irregular animation technique that relies partly on AI-driven simulations, rather than manually-controlled movement. The result, an unpredictable clash of realistic and utterly broken motion, accentuates the film and its message of embracing life's random and beautiful peculiarities.

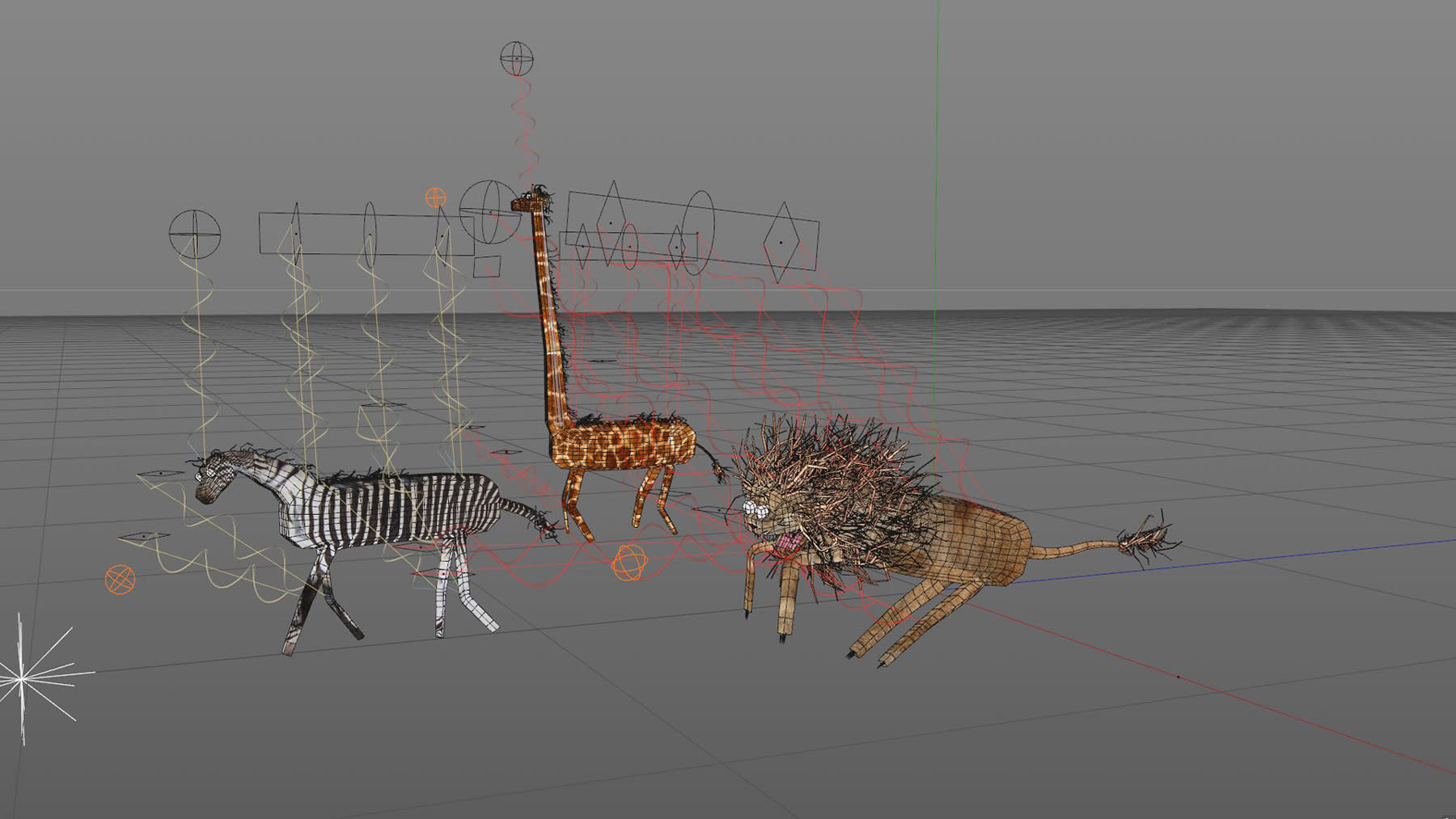

Director Nikita Diakur and Redbear Easterman. In 2013, director Nikita Diakur wasn't thinking about obscure animation techniques; he just needed an idea. The filmmaker had returned to Mainz, Germany, in 2010 after completing a master's degree in animation at London's Royal College of Art. Three years later, and desperate for some creativity, he Google-searched "inspiration" and found a website dedicated to inspirational quotes. A few clicks later and he was reading a story about a real-life tomcat, Ugly, who sought compassion until its last breath. "It didn't really connect with me at first," he said. "It was just funny to me. But the message of the story was very strong. And I felt that it needed to be told in a way that people like me could get connected to it." "It didn't really connect with me at first. It was just funny to me." Some visual elements, such as the snow-capped mountains, fell into place immediately. The stark, cuboid buildings were based on Moscow, where he grew up, and Mainz. Redbear, meanwhile, was based on relaxing YouTube videos filled with Native American music and poetic quotes such as: "The end will be as in the beginning, and this was beautiful, the heart pounding in the drums." Other ideas, though, took a little more time to formulate. "It's like when you move into a flat," he said. "Good flats become nice over time. You can't really decorate the flat completely on the first day, it slowly develops. And that's what happened with Ugly as well." At first, Diakur was interested in simulated animation as a way to accelerate his workflow. In video games, developers use sophisticated physics engines to portray complex explosions and natural effects on screen. The fledgling director wondered if the same technique could be applied more broadly to 3D animation, removing the need to meticulously move characters and objects. 'Ugly' uses simple shapes to portray fire, water and other elemental effects. He did some research but couldn't find any animators who had used the technique for the bulk of their work. So the director started experimenting with a feature called Dynamics inside Cinema 4D, a popular 3D-modeling, animation and motion-graphics application. The feature allows animators to quickly simulate movement with believable or, if the project requires it, unrealistic physics. It's typically used to portray complex collisions -- an old temple caving in, or a box of toys falling over -- where traditional keyframing would be too difficult or time-consuming to complete. Animators usually assign one of two properties to their assets: a rigid body, which means it will move around and generally obey gravity, or a collider body, which creates immovable surfaces for objects to interact with. In a basic scene, you might pour a bunch of rigid body balls down a set of collider body stairs. Diakur, however, applied Dynamics to every human and animal in Ugly. They all comprise rigid body limbs that were cobbled together with various ball-and-socket-style connectors. In motion, though, they all crumpled to the floor like ragdolls. To solve this problem, Diakur attached invisible, spring-like wires to all the major limbs, turning the characters into energetic marionettes. Finally, the strings were connected to controllers that could provide limited guidance to the figures.

Diakur used invisible wires to gently guide the characters. "I was a bit scared because nobody had used it," Diakur recalled, "and I was thinking it's probably for a reason that nobody has used it because it's so difficult to control." The setup created some artificial distance between Diakur and the cast of Ugly. He could instruct the characters to move, but what actually happened at the end of the strings was chaotic and, sometimes, seemingly random. Cinema 4D was trying to figure out, or simulate, how all the parts should be moving through the scene. Dynamics was never built for such a purpose, though, and the sheer number of variables created erratic responses. "If you want to animate a walk cycle, for example, then you have to make a hooping motion for the feet through the controllers," Diakur said. "These give a command through the wires to the limbs, which start interacting. Then it's up to the [simulation's] calculations to decide what it's actually going to do with it." The birds in 'Ugly' were controlled with wires attached to each wing. Diakur achieved some motion with invisible motors that could shunt cars and motorcycles around the scene. He also used invisible fans, or miniature tornadoes, to gently guide objects in a helpful direction. Most of the time, though, the young director was at the will of his digital puppets. They behaved more like actors on a film set, or the inhabitants of a sprawling video-game world like Grand Theft Auto V. Diakur had to shoot around them, replaying and tweaking the scene until it lined up with his original vision. "You try one take, and it either works or it doesn't," he said. "You repeat it until it works perfectly. It's kind of a process." A laborious process... but it produced many "happy accidents" that wouldn't have been possible with a traditional animation workflow. During the first dream-like sequence, for instance, some of the animals stretch and morph as they knock into each other and brush against the foliage around them. Later, the camera jumps to a merry-go-round with a spiky, almost unrecognizable human in the middle. The strange sight -- a consequence of clothing that the simulation can't keep up with -- rapidly expands and takes over the screen, creating a unique fade to black. "It depends on the kind of story you want to tell," Diakur said. "Do you want to have a glitch in the foreground? Do you want people to react to the glitch? Because, if so, the glitch is important. But if you have a character doing something [important] that needs to be in there, and then something explodes, then obviously you have to take it down and get rid of the glitch." "Suddenly it felt like it wasn't just my mom watching the project." Two years into the project, the Russian-born filmmaker needed cash. He had followed the astronomical successes of movies like Kung Fury and the infamous potato-salad project on Kickstarter. By that point, though, the platform had matured and people were growing increasingly skeptical about new pitches. Diakur and his collaborators would only get one chance to win them over, and spent the better part of six months perfecting a page full of gorgeous GIFs and explanatory videos. They also promised a range of rewards for people who pledged above €5, including t-shirts, vinyl records, posters and toys based on Ugly the cat. The campaign was successful, raising €10,829 (roughly $12,290) from 206 backers. It was enough to cover some, but not all, of the remaining costs associated with the film. Diakur was still happy, though, because the Kickstarter had created a following that was now anticipating Ugly's release. "Suddenly it felt like it wasn't just my mom watching the project, but people I didn't know," he recalled. "It's always very motivating and very cool to see that somebody is interested in what you're doing. That you're not just in your back room animating and hoping that somebody likes it in the end. People are really waiting for it to finish." Some glitches were kept in the film for comic relief and narrative effect. Ugly was completed on March 8th, 2017, and released to backers online. The film was then shown at a number of film festivals later that year, starting with Animafest Zagreb in Croatia. It was praised by viewers and quickly received a bunch of accolades including the New Talent Award at Fantoche, the Animated Encounters Grand Prix Award 2017 and the Nelvana Grand Prize for Independent Short at the Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF). The last two happened on the same day and caught Diakur completely off guard. "It was super," he said. "Just like a happy punch in the face. Kind of. It was a very nice moment." The awards helped Diakur to fund his next project. In Germany, young directors can apply for cash using a points system that is tied to film-festival screenings and awards. Diakur's aim, therefore, was to show Ugly at every event that would attract credits and, by extension, government money. Some of these festivals, though, have strict premiere requirements that temporarily block directors from releasing their work online. That's why Ugly didn't premiere on video-sharing site Vimeo until July 24th, 2018, more than a year after production had ended. That timeline will have confused some viewers. The director was approached by Adult Swim, the US programming initiative behind Space Ghost Coast to Coast and The Brak Show, to produce a short using the same animation technique. The result, a zany dance sequence called Fest, was released on YouTube, Vimeo and Facebook in late February, months before the public had seen Ugly.

Redbear Easterman pets Ugly the cat. Diakur has enjoyed reading the comments on both videos. "Some people say they didn't really get Ugly in the very first viewing, while other people have come to me and said that they got goosebumps, or even cried during the film," he said. It'll be interesting to see if other people adopt the technique, or whether Diakur will continue as the sole pioneer of this strange but oddly beautiful form of animation. The young director says he isn't done with the concept and would like to try an Ugly video game in the future. He's also considering a feature-length movie that expands on his unusual workflow inside Cinema 4D. "It's a really crazy idea, and I think now could be a time to actually try and make it happen somehow," he said. "So I'm kind of developing that, but let's see. I honestly don't know." Credit Sources: Nikita Diakur Source: Ugly, Nikita Diakur

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2OJOCGl |

Comments

Post a Comment