E-readers have become one of the most pervasive pieces of tech for many reasons. They survive alongside tablets because they're accessible -- Amazon's entry-level Kindle is just $80 -- and don't require daily charging. E-ink displays don't strain your eyes nearly as much as backlit screens, nor do they keep you up at night. Above all else, though, they can hold the entire works of Shakespeare countless times over while being thinner and lighter than any paperback. But this idea of portability, of condensing the written word into a format only a device can understand, is older than The Great Gatsby. It can be traced back to the early 1920s, and the invention of the Fiske Reading Machine. Bradley Allen Fiske, born 1854, had a long and illustrious career in the US Navy, peaking at the rank of rear admiral. Fiske wasn't just a naval officer, but a serial inventor. He's credited with many advancements in warfare technology, masterminding telescopic sights for ship artillery, an electric range finder, motorized gun turrets, as well as radio control and aerial launch systems for torpedoes. The list is exhaustive. And when he retired from service in his early 60s, a year before the US became involved in World War I, his passion for invention did not abate.

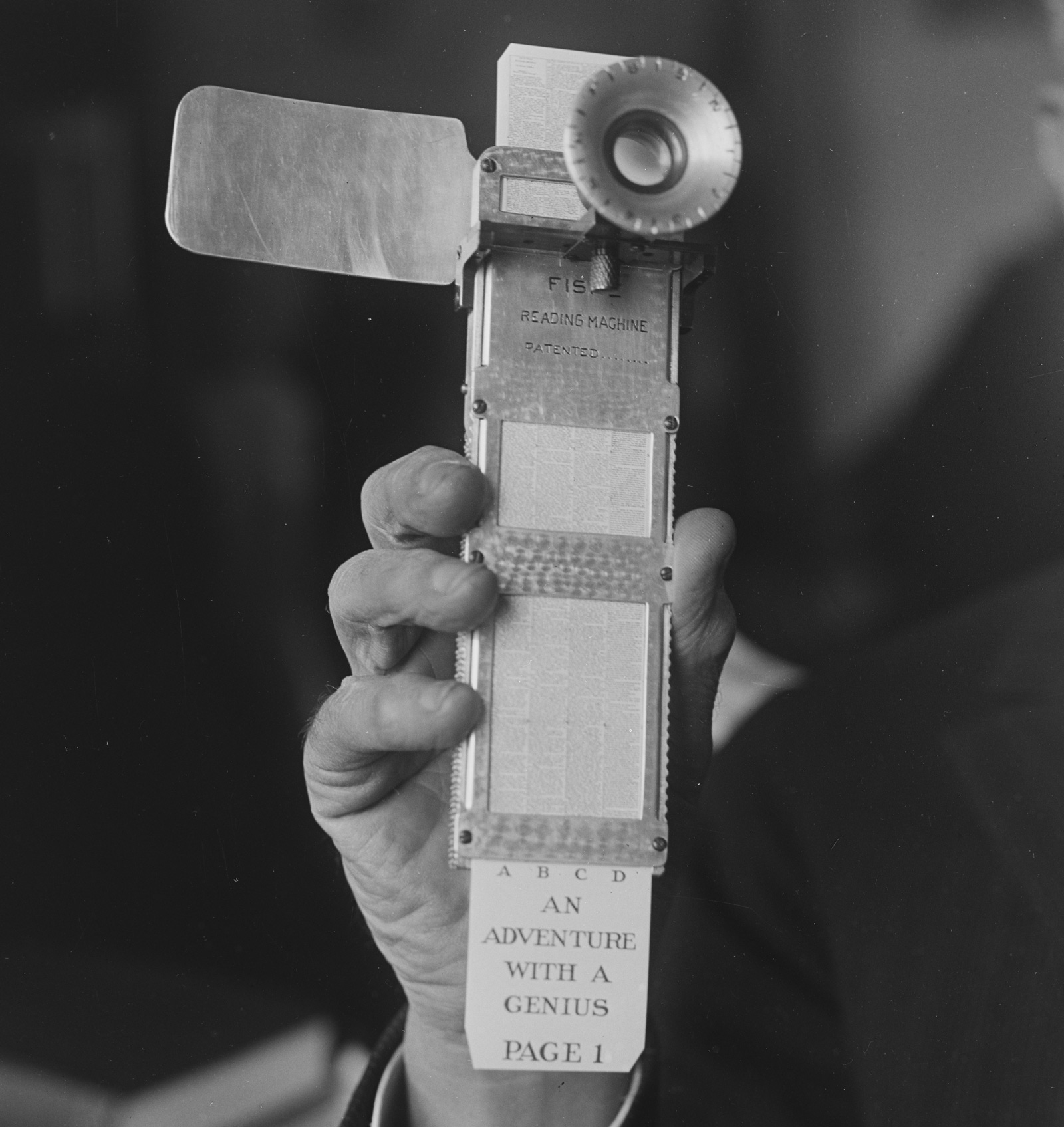

From a 1922 edition of 'Scientific American' The stories behind many early inventions and concepts are somewhat lost in time, but not Fiske's Reading Machine. Whether it was down to his long naval career, his pedigree as an inventor or the unique nature of the contraption itself, Fiske's device captured the imaginations of his era. In 1922, his machine was covered in both Scientific American and Science and Invention magazines. Later articles appeared in The Miami News and Popular Mechanics magazine in 1926. The Reading Machine was a metal, handheld device featuring a magnifying lens for one eye and a shield to mask the other. Using photo-engraving techniques, Fiske miniaturized printed texts onto cards roughly six inches high by two inches wide, far too small for any standard press to produce or human eye to read. A user would insert the card into the machine and read it through the magnifying lens, moving both the card and the eyepiece to switch between several columns of print. It was a simple but elegant way of compressing any text into something pocket-sized. To demonstrate the idea to journalists, Fiske condensed the first volume of Mark Twain's Innocent Abroad (a book of roughly 93,000 words) into 13 of these cards.

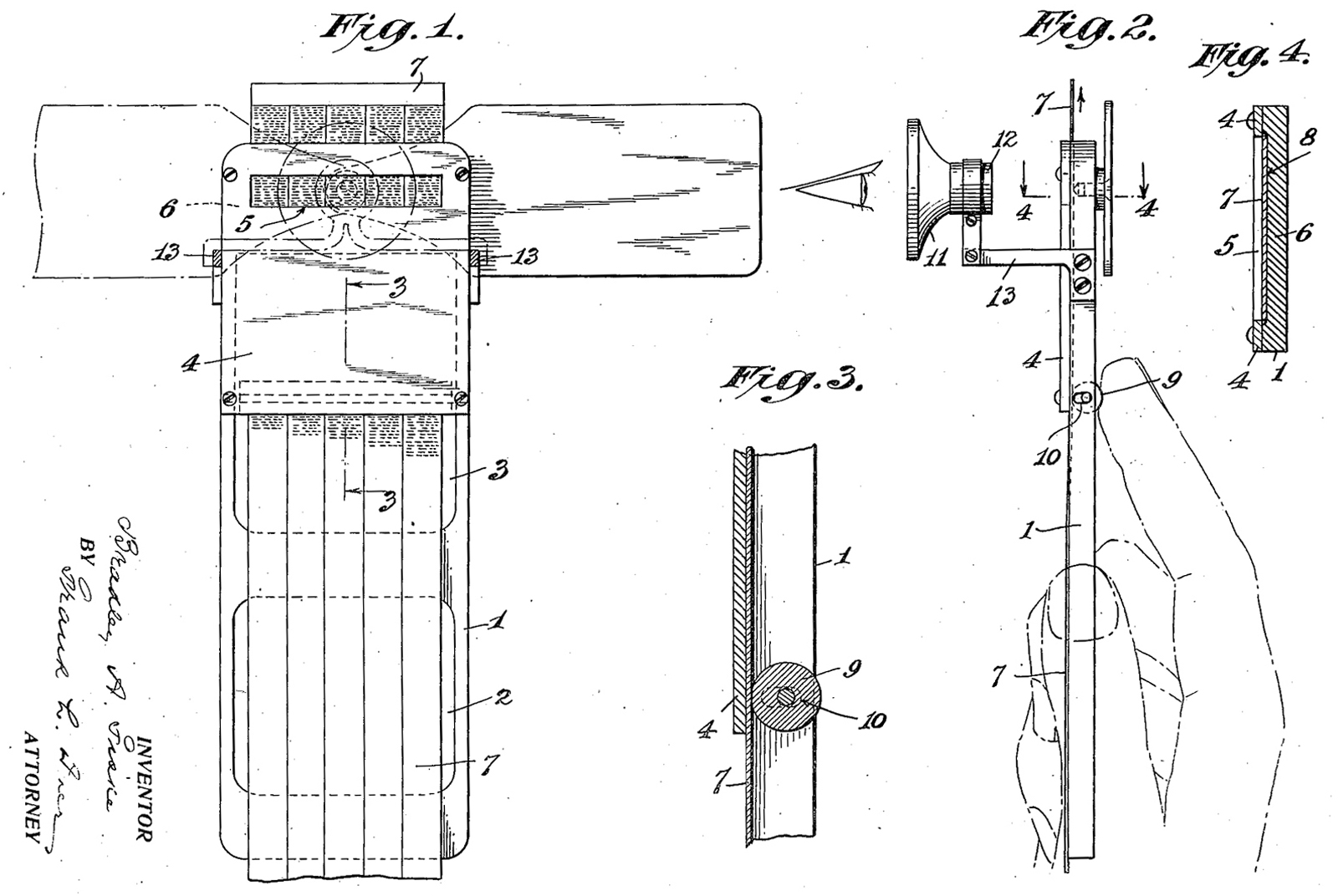

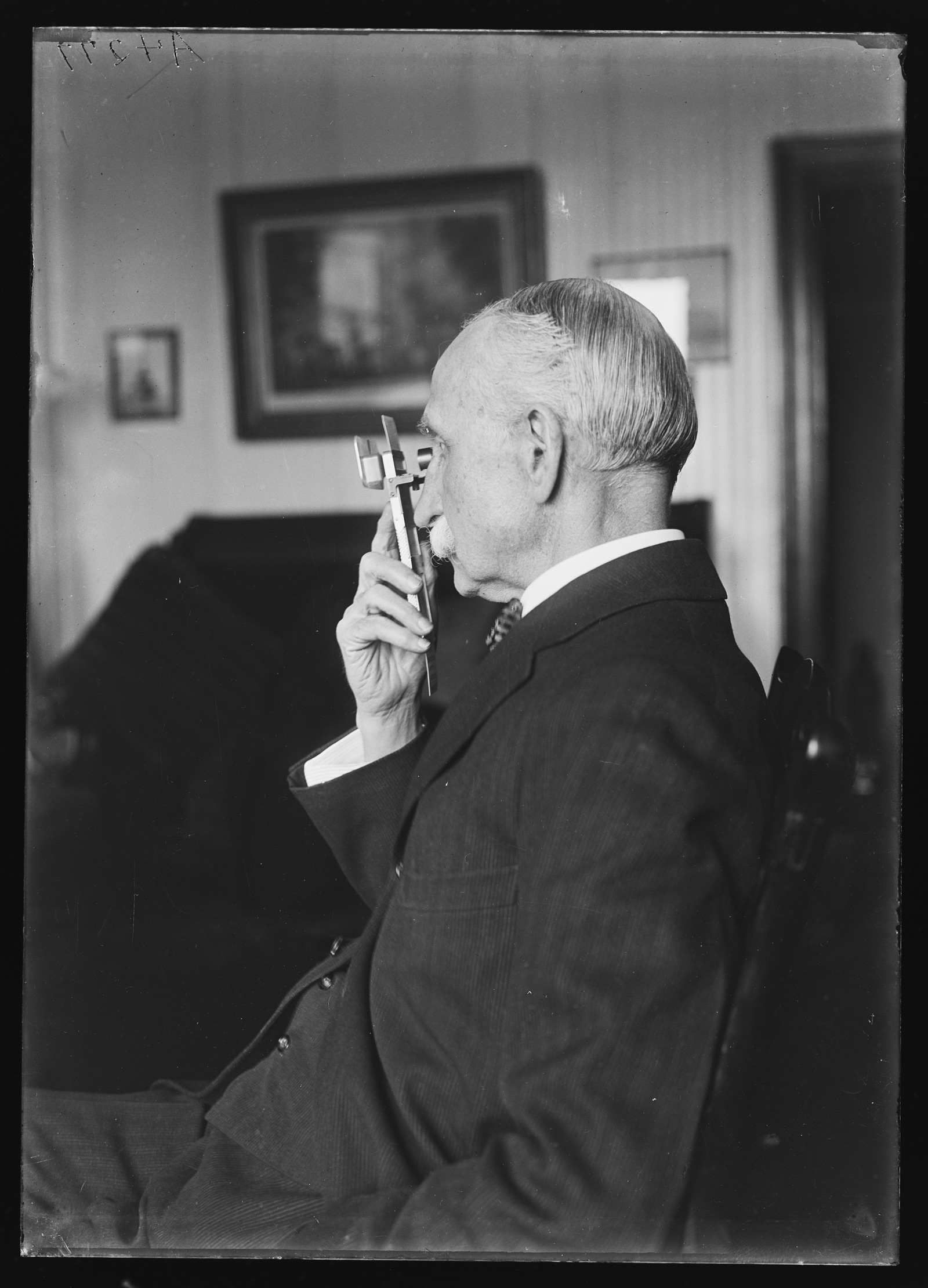

Credit: Harris & Ewing (circa 1921) / Library of Congress Fiske believed he had single-handedly revolutionized the publishing industry. Thanks to his ingenuity, books and magazines could be produced for a fraction of their current price. The cost of materials, presses, shipping and the burden of storage could also be slashed. He imagined magazines could be distributed by post for next to nothing, and most powerfully, that publishing in his format would allow everyone access to educational material and entertainment no matter their level of income. Fiske filed at least 11 patents for his Reading Machine between 1920 and 1935. He experimented with various designs, the earliest of which used spools of paper rather than the cards that became his preferred format. He also manufactured at least a few different prototypes, one of which is under the care of The Rosenbach Museum & Library in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Fiske's Reading Machine never graduated to mass production, despite the press attention.  One of Fiske's many patents US Patent Office At the same time Fiske was iterating his Reading Machine, microfilm was beginning to catch on. Though microphotography was first popularized in the late 1850s, it wasn't until the 1920s that it started being used as an information storage medium. While it initially found its feet in the business world -- for keeping record of cancelled checks, for example -- by 1935 Kodak had begun publishing The New York Times on 35mm microfilm. It subsequently became the archiving standard, but the appetite for miniaturized novels and handheld readers never materialized in the way Fiske had imagined.  Ángela Ruiz Robles with her 'Enciclopedia Mecánica' The Ruiz Robles family via Wikimedia A few decades later in 1949, Spanish teacher Ángela Ruiz Robles enjoyed 15 minutes of fame for her invention, the "Mechanical Encyclopedia." This was a slightly more elaborate method of condensing information, using scrolls and various mechanisms to cram text and audio into a small briefcase that could replace several books if fed with different inserts. It wasn't until 1971, when Michael Hart used the University of Illinois' Xerox Sigma V mainframe to digitize the Declaration of Independence (the genesis of Project Gutenberg), that the idea of e-books as we now know them was born. Announced in 1991, Sony's Data Discman was technically the first e-reader, and was followed that decade by several successor devices with monochrome LCD displays. At the same time, through the mid-to-late '90s, researchers at MIT were developing the "E Ink" display -- the last piece of the e-reader puzzle. Though we probably would've got here eventually, owning Kindles and Kobos and Nooks with entire libraries stored on them, Fiske saw it all coming, 80 years earlier.

Credit: Harris & Ewing (circa 1921) / Library of Congress

Technological innovation didn't begin with the development of the first integrated circuit in the 1950s. Backlog is a series exploring the era of possibilities: engineering feats that followed the industrial revolution, quirky concepts the future's rendered obsolete, and inventions that paved the way for some of the technology we use today.

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2zf5a65 |

Comments

Post a Comment