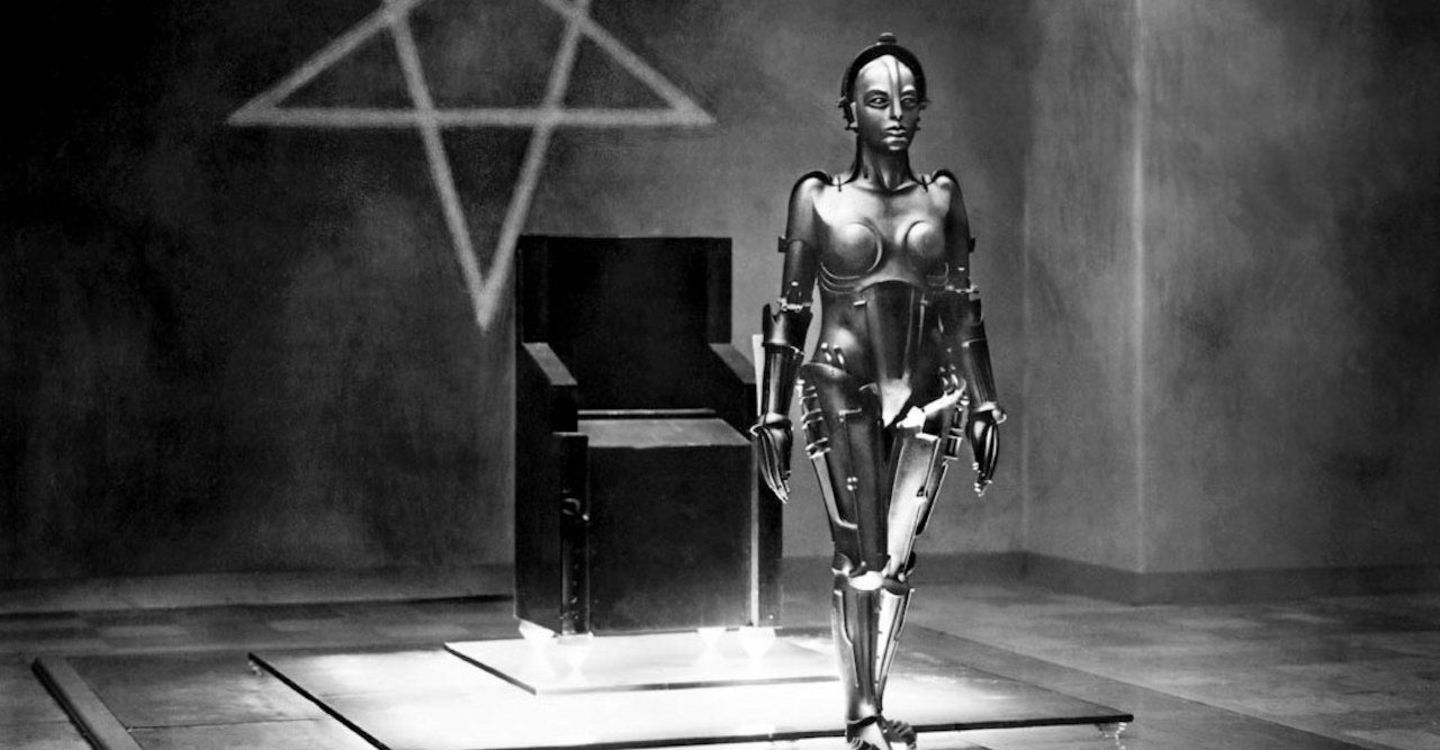

Dr. Oz isn't happy about the future of sex. The day I'm scheduled to appear on his show, the television physician and Oprah protege has assembled a cast of victims and villains that includes a college communications major who caught chlamydia from a Tinder date; a 24-year-old woman who was stabbed 21 times by the fiance she met online; and Douglas Hines, a cartoonish engineer donning a white lab coat and outsize bowtie, who claims to have created the world's first sex robot. NSFW Warning: This story may contain links to and descriptions or images of explicit sexual acts. I'm here, presumably, to act as a voice of reason in a segment called "Rise of the sex robots: Why experts are issuing warnings!" My co-panelists, a sex therapist and a psychologist, are well-trained in the art (or is it science?) of near-scripted debate. While one is slightly more optimistic, their arguments are essentially two sides of the same coin: Sex robots either can or will pose a threat to human relationships, or worse. As TV doctors do, they've both developed firmly planted opinions on the subject without any first-hand experience. It's not lost on me that I'm the only one in the room who's actually seen a sex robot IRL. After the doctors deliver their warnings, Oz turns to me, a look of concern written in deep lines across his forehead. He wants to know if people can have real, intimate relationships with robots. The answer is simple: not yet. For the past two years, I've followed the birth of the sex robot and the surrounding media frenzy with a burning curiosity. I've spoken with the men and women who have dedicated their lives to the study and development of these machines. I've spent countless hours devouring the many books, movies and television shows that laid the groundwork for their creation and gone hands-on with Harmony, the world's first market-ready sex robot. As Abyss Creations, the entity behind the RealDoll, prepares to unleash its sex robot on the world, just about the only thing I haven't done is have sex with one. I did manage to take three of them out for dinner, but let's not get ahead of ourselves. Hands-on with Harmony at CES 2018 The first-generation RealDollx will be offered as a modular robotic head that can be paired with most existing RealDoll bodies. It can move its head up and down and side to side, blink, smile and raise its eyebrows. With the help of an Android app, it can hold limited two-way conversations and simulate orgasms. Users will be able to customize their doll's personality and select from two preloaded avatars at launch: Harmony and Solana. Their faces and bodies are fully customizable, and customers can select from a menu of 11 swappable vaginas and hundreds of nipple variations. So far, Matt McMullen, the founder of RealDoll, says he's sold six of these robots, but their reputations precede them. Over the past couple of years, sex robots have taken on an outsize role in popular media. Everyone from The New York Times to the BBC has found a way to wedge these largely nonexistent machines into debates around everything from gun violence to child sex trafficking. According to recent accounts, you can buy sex robots that look like children, celebrities, even the deceased. They offer a "rape mode" and bionic penises, and operate entire brothels in Europe and Asia. One Gizmodo headline went as far as to suggest that "Sex Robots May Literally Fuck Us to Death." I wanted to get a grasp on why the sex robot has become such a divisive symbol in popular culture. So I flew to England, about a month after my daytime-TV debut, to meet the two women at the center of the sex robot debate. Kate Devlin and Kathleen Richardson couldn't be more different. Devlin is a senior lecturer at Goldsmith's University of London, where she studies human-computer interaction and runs an annual sex tech hackathon. Richardson serves as professor of ethics and culture of robots and AI at DeMumfort University, where she launched the now-infamous Campaign Against Sex Robots in 2015. Where Richardson has positioned herself as a sort of 21st-century Carrie Nation, calling for sexbot prohibition, Devlin has toured the country preaching a gospel of acceptance. She believes that sex robots don't have to look like humans, that they can and should be gender-nonspecific. They could even serve as a deterrent to sexual abuse and violence. Richardson, on the other hand, thinks they should be stopped before they ever get started.  People want to believe that these things exist because we've been primed by so many years of films, so many years of reading books. And I think the media isn't portraying the reality of it because there's not so much of story in that. Dr. Kate Devlin Evil Maria or the Maschinenmensch in Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis, one of the earliest depictions of the sex robot in film. In her home office, just steps away from the River Thames, Devlin is finishing the final chapters of her book: Turned On: Science, Sex and Robots. For all the doomsday scenarios surrounding her pet subject, Devlin is lighthearted and optimistic. For the past two years, she's served as a measured, objective voice in an increasingly sensational debate. If you ask her, sex robots aren't much of a threat at all, largely because they don't really exist. "It's a really compelling narrative," Devlin says. "This idea of a sex robot. I mean, that's super-exciting, super-scary. People want to believe that these things exist because we've been primed by so many years of films, so many years of reading books. And I think the media isn't portraying the reality of it because there's not so much of story in that." The hype is fascinating. The reality, to Devlin's point, is quite a bit less glamorous. Hines' Roxxxy, with all of her customizable personalities (Frigid Farah, Wild Wendy and S&M Susan among them), has frequently been singled out as a fake, a sort of Mechanical Turk for the sex robot era. Samantha, the product of Spanish tinkerer Sergi Santos, can't even open her mouth or move her head. McMullen's RealDollx is the most sophisticated of the bunch, but even it has its limitations. Truth be told, the closest thing we have to the hosts of Westworld can't even stand up on its own, let alone fuck us to death. When I met the original RealDollx, Harmony, for the first time, I was immediately transported to the uncanny valley. She was crafted with such care, such attention to detail that, at a glimpse, she was indiscernible from a human being. As she lifted her eyelids and opened her mouth to speak, I found myself slack-jawed, at a loss for words. It wasn't until Harmony introduced herself that the reality set in. Her lip sync is far from perfect and you can hear the motors whirring inside her head. Her smile is subtle, as are other small facial expressions, but her head moves with the staccato of a sprinkler. As with its mainstream counterparts, like Siri and Google Assistant, Harmony's AI often gets hung up on natural speech. My first time meeting Harmony. Harmony is inanimate from the neck down. Her skin is cold to the touch. Her artificial intelligence, while impressive, is still limited. She requires an Android app to communicate and her battery lasts just two hours. Once she runs out of juice, she's tethered to an outlet. She isn't the fantasy that we've been taught to expect. Harmony is a first-gen device with niche appeal. Even McMullen admits that his robotic companions likely won't be a mainstream success. So, what's with all the hype? "I think the media is focusing on fear, which is a very natural thing to do when technology advances," Devlin says. "People are scared of technological change. Here's another element of your life that will have a robot in it. It's not enough that your job is gonna be lost to automation, now your relationships will go that way, too. That's a really deep fear to kind of tap in on." It's hard to believe that anyone could truly create a human-like bond with Harmony or Solana, as Dr. Oz suggested, but Devlin says, "It's not very difficult to bond with a machine." Devlin cites the work of Clifford Nass, a Stanford University Professor, whose 2010 book The Man Who Lied to his Laptop, explores the ease with which we form attachments with machines. Nass found that computers don't even really have to take on human traits for us to treat them like humans. In her 2013 paper "Extending Legal Rights to Social Robots," Dr. Kate Darling, a research specialist focused on human-robot interaction at the MIT Media Labs, dives deeper into those attachments and their implications. She points to a number of scenarios in which social robots that look far less human than Harmony have elicited emotional responses. There's the case of the US Army colonel calling off tests of an insect-like robot tasked with detonating landmines on the grounds that the trials were "inhumane," and instances of Sony Aibo owners reporting feelings of guilt when they put their robotic dogs back in the box. The bottom line is, you may not be ready to fall in love with a robot, but chances are, you already have an emotional attachment to your smartphone. This is exactly what Kathleen Richardson is afraid of.

Two RealDollx bodies hang from the ceiling of the Abyss Creations studio. A couple hours north of London, at DeMumfort University, Richardson is finishing a book of her own, titled Sex Robots: The End of Love. Until today, my perception of Richardson has been based solely off bombastic TV interviews, a wobbly TedX talk and the sensationalistic Campaign Against Sex Robots. Over the course of my six-hour visit, though, I'll get to know a much more level-headed human being whose ideas aren't nearly as radical as they seem. That said, Richardson has the regrettable tendency to compare sex robots to slaves. She believes that sex work is inherently nonconsensual and that sex robots will lead to increases in human trafficking and child molestation. On those points and others, I couldn't disagree more, but she touches on some very real anxieties about the rise of AI. Throughout a relatively scattered and meandering conversation on the dangers of sex robots, she keeps coming back to one theme: the supremacy of humans. She believes that we are special, and the things that make us human should be protected. "I need to be clear that I think a robot is a tool and human beings are extraordinary," she says. "We create tools and use tools and those tools enable us to live different kinds of lives. That's not my concern. You know, this is not a campaign against robots or tools or hammers or chisels or any other manner of things. This is a campaign against the idea that human beings can be compared to machines, analogous to machines." "I think Harmony is a misogynistic creation by someone who is a misogynist." The Campaign Against Sex Robots isn't an attempt to stave off a Westworld-style robot uprising. For Richardson, it's about drawing a line between humans and goods. Still, her campaign stokes the flames of uncertainty. In her many talks and interviews, she paints a picture of a future where humans live increasingly isolated, unfulfilled lives, where human trafficking and child abuse run rampant, where gender inequality flourishes. And it all comes at the hands of the sex robot. "Because they arise out of the fundamental inequality, they'll just reproduce it. So, they'll just reflect back to us the objectification of women and girls, the sexual objectification of women and girls," she says. If Devlin and Richardson have anything in common, it's a shared belief that the current crop of sex robots is harmful to women. So what do they think of Harmony? Devlin's take is complicated. When she toured Abyss Creations last summer, she was struck by the sophistication of Harmony's AI and appearance. "I expected that I would really hate it because of its very sexualized female form but actually I just was so incredibly impressed by the level of skill that goes into them," she says. Richardson, who's yet to meet McMullen or his inventions in person, isn't pulling punches. "I think Harmony is a misogynistic creation by someone who is a misogynist."  AOL McMullen knows the critiques that have been leveled against him, and he's ready to put those accusations to rest. When I returned to Abyss creations just weeks after my trip to the UK, he was eager to show me his latest project. Henry is the natural successor to Harmony and Solana, a 6-foot-tall white male sex robot with Alpaca hair eyebrows, washboard abs and a swappable cock and balls. He won't be available until early next year, and he won't have a bionic penis as the British tabloid The Daily Star reported in January. Henry is under construction. The first time that I see him, McMullen's team is still piecing together his skull from 3D-printed parts. His body is on loan from the RealDoll archives. The next day, McMullen will put the finishing touches on his rippling muscles and in a few months, after Harmony and Solana make it to market, his team will set to work on Henry AI. McMullen created Henry to prove a point about representation. If he makes a male sex robot too, how can he be misogynist, right? To his credit, RealDoll already has a very diverse pallet to choose from, and the RealDollx will be just as customizable. Everything from skin tone to nipple size and even gender is up for negotiation. In the end, though, there's no escaping the objectification argument. McMullen is quite literally selling the female form as a sexual object, whether Henry exists or not. Or is he? As long as I've known him, McMullen has contended that Harmony is so much more than a sexual object. To his mind, the term sex robot is a self-serving media invention. He says the primary functions of RealDollx are conversation and companionship. Sex is secondary. He sees a future where his robots will one day be able to serve as receptionists, even caregivers. It's the media that can't let go of the whole "sex robot" narrative, and with good reason. Media created it. If you ask Devlin or Richardson, or just about anyone who's ever studied the origins of the sex robot, they'll point back to some form of popular media. Most of the origin stories start in Ancient Rome with Ovid's sensitive misogynist, Pygmalion. The lovesick sculptor, disillusioned by the shortcomings of human women, fashioned himself an ivory companion that he kissed, caressed, slept with and eventually willed to life. Since then, the trope has been repeated endlessly in books, TV, movies, opera, ballet, you name it. But it was a call from The New York Times that actually brought Harmony to life. McMullen recalls feeling restless. After 20 years of being the RealDoll guy, he found himself looking for something more. He told his wife that he didn't want to just "make another doll with another pair of boobs." So she told him to make a robot instead. But McMullen is an artist, an ideas guy, not an engineer, and besides, he says, "this is like, a serious thing to do -- you know, it's like rocket science or brain surgery." He kept coming back to the idea, but he didn't see how he could make it happen. "I think that human beings need real relationships, and will always need those." Then he met Susan Pirzchalski and Kino Coursey, a married couple from Texas. Pirzchalski, a hardware and software engineer, had bought Coursey a RealDoll for finishing a Ph.D. in computer science, and the two set to work on what would become the first iteration of RealDollx. When they finally had a prototype they reached out to McMullen, who started supplying the couple with spare parts. About a year after McMullen met Pirzchalski and Coursey, a Brazilian entrepreneur named Guile Lindroth paid him a visit. Lindroth was looking for a doll that could embody NextOS, a virtual assistant he'd been shopping around Silicon Valley with his co-founder Yuri Furuushi Machado. "We all kind of had the same vision," McMullen says. "It wasn't until I agreed to do The New York Times piece that things kind of got accelerated. They asked me, 'Are you building a robot?' And I was like, 'Yeah, we're, we're working on it.'" In reality, there were no official plans for a robotic RealDoll, but McMullen committed to a shoot in six weeks' time. So he called Pirzchalski and Coursey, who recommend he check out NextOS. "I said, 'I actually know the guy, I met him.' So, I called Guile and asked if he would join us, and we all kind of converged on that New York Times piece, and that was where it all started." On June 11, 2015, The New York Times published a short video called "The Uncanny Lover," and the sex robot was born. That September, The Washington Post reported that a researcher in England named Kathleen Richardson had just launched a campaign against robots, and the next week, I was on the phone with McMullen making plans to fly him to Las Vegas for a live interview at CES, the world's biggest consumer-electronics show. At the time he was humble, even modest. He said he didn't see Harmony as a mainstream product and didn't see how, as Richardson suggests, sex robots could pose a threat to humans. "I can think of dozens of other robotic applications that are far more concerning than a sex robot, for one," he said. "Secondly, I think that this kind of product, the sex robot as a concept, is not something that everyone will be attracted to or find appealing. So I don't think, in the bigger picture of things, that it's going to have any kind of negative implications for real relationships. I think that human beings need real relationships, and will always need those." For the next two years, McMullen and his team continued to develop the AI and robotics and as he came closer to releasing the world's first real sex robot, the media hype machine went into overdrive. My Dr. Oz co-stars weren't the only ones issuing warnings. A host of blogs and tabloids laid the panic on thick, and the mainstream media piled on. I found myself increasingly annoyed at the speculation and sloppy reporting coming out of even the most respectable institutions. So I reached out to McMullen with a request. I wanted to have sex with one of his robots.

Henry, Solana and Harmony en route to the country club. The answer was no, but he was willing to compromise. So we settled on a dinner party. McMullen's wife, Lily, and my producer, Olivia Kristiansen, took care of the details, it was up to me to take care of the guest list. I invited a couple of friends up from San Diego and they promised to bring another couple. I was intentionally light on the details. I gave them the time and location and said we'd be hanging out with people from RealDoll and their sex robots. The night started off as I'd expected. We'd landed on a dimly lit private dining room at a lakeside golf resort. By the time the guests of honor had been wheeled through the restaurant, propped up at the table and connected to Bluetooth, word had spread that something strange was going on. Middle-age women with large glasses of white wine were falling all over themselves to get a glimpse inside, and our waitress was beside herself with excitement. Considering all of the buzz around our arrival, I'll admit I was expecting something more. I'd spent the better half of two years shooting down the hype, but halfway through my second martini, I was ready for Henry to get up and give my guests a show. Instead, the first-generation sex robots acted just as they should. They interjected in conversations without prompting, failed to answer simple questions and mostly sat idly, occasionally blinking and turning their heads in an attempt to show signs of life. After a couple of glasses of wine, my friends settled in and the robots transformed from guests into conversation pieces. "Are they all virgins?" "Do you need testers?" "Is this what Thanksgiving looks like at your house?" By the time dessert was served, Henry and Solana were half-naked, and any illusion that we were just a group of fully autonomous humans sitting down to a sophisticated dinner at the country club had disappeared. Selfies were taken, jokes were cracked and the sex robots were manhandled. The responses were largely positive -- people were, unsurprisingly, amused, but this wasn't a night of great revelations. No love connections or sales were made. No lives forever changed (at least as far as I know). That night, Harmony and her friends served as incredibly elaborate props -- the ultimate party tricks.

I have no doubt that Harmony and the rest of the RealBotix family will make some people very happy, even in their current state, but there is no Ex Machina-style reveal to be had here. Ultimately, these machines are no more dangerous or awe-inspiring than a Roomba, technically speaking. Of course, this is just the beginning. McMullen and his team are already hard at work on RealDollx 2.0. Henry is set to ship early next year, followed by hardware and software upgrades for the whole family. Among other things, they're toying with the ideas of self-lubrication and an internal heating system. But don't expect RealDollx to bring all of the media's wild speculation to life. McMullen is saving that for his next act. He's partnered with a Canadian artificial-intelligence firm with a Silicon Valley pedigree. The eerily dystopian Sanctuary AI plans to create fully autonomous humanoid robots that are indistinguishable and independent from human beings. The people at Sanctuary are tight-lipped about their plans. They don't want to be misconstrued for a sex-robot outfit, although they do intend to make their humanoids anatomically correct. As hard as I try, I can't help but think of the worst-case scenario; the endless depictions of rogue sex robots, who turn on the people who created and took advantage of them. I think back on the dinner party, on Solana sitting bare-chested at the dinner table while my friend and I groped at Henry's crotch, the wine flowing, the laughter, the robots devoid of agency. It triggers the feeling I had the first time I saw Harmony open her eyes, a sense of uncertainty and a sense of unease. What will happen when the machines really are like us? I want to be the same level-headed version of myself that I played on Dr. Oz. I want to tell myself and everyone else that there's nothing to worry about. I want to believe that these are just machines, that the hype isn't real. But I can't. If all of the outlandish stories, dystopian narratives and over the top warnings about sex robots tell us anything, it's that humans fear the unknown. I'm afraid I'm only human.

via Engadget RSS Feed https://ift.tt/2kNGVSr |

Comments

Post a Comment