'Into the Breach' is monsters, mechs and a reset for strategy games

Subset Games' 2012 space command simulator FTL wasn't the first roguelike indie game to come out during the subgenre's renaissance, but it stood out from the rest. Players guide their single ship against a galaxy of enemies, and the challenge and high skill ceiling earned legions of fans and financial success. Last February, the studio teased its second game, Into The Breach, a grid-based strategy game where the player's trio of mechs must fight off an invading onslaught of colossal bugs while saving as many people as possible. The game comes out today -- and anyone that loved the studio's tough-but-rewarding first game will be equally charmed by its sophomore release.

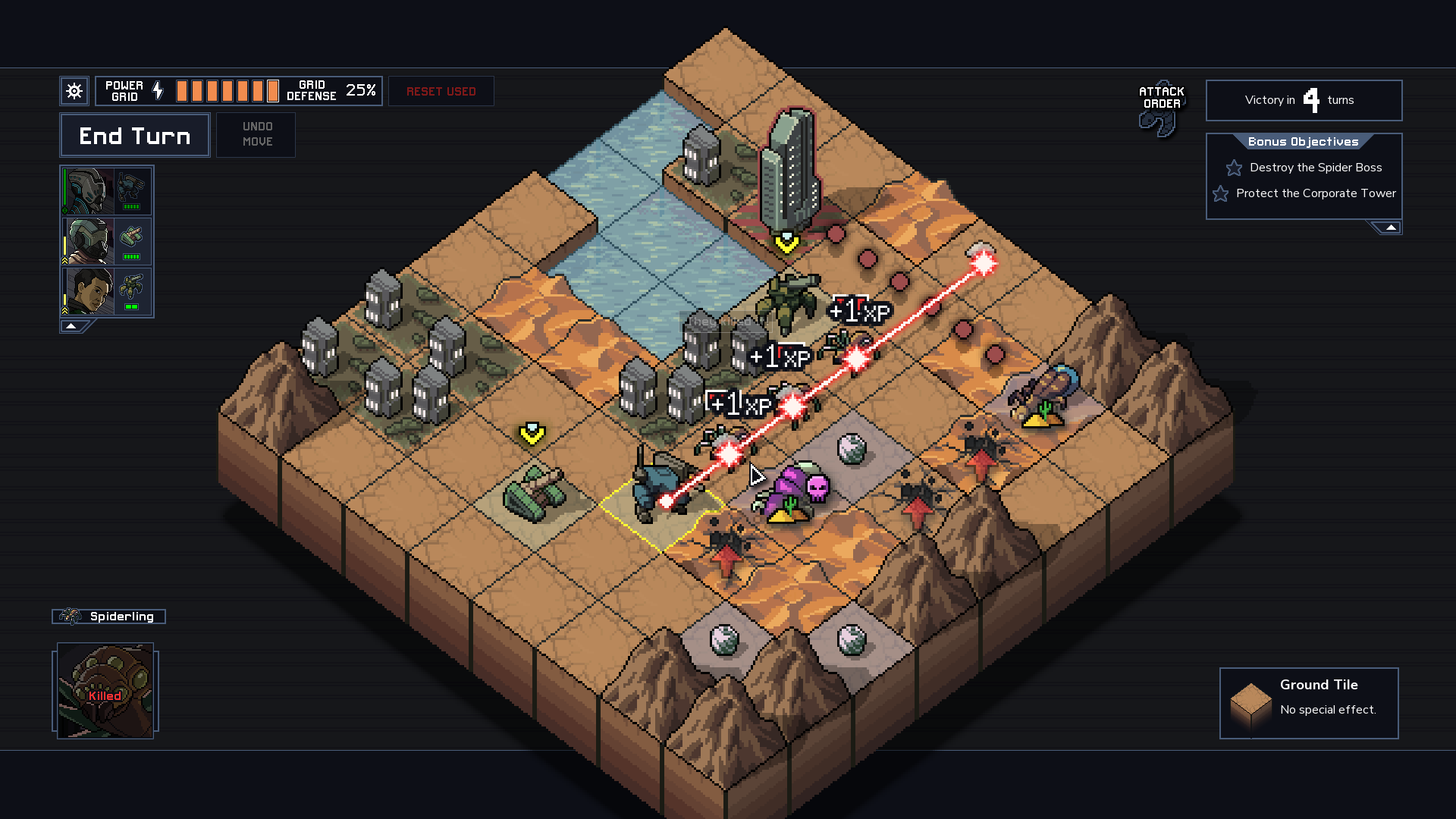

Into The Breach is a turn-based strategy game where mistakes are costly and character death is permanent. It takes cues from similarly unforgiving titles like XCOM and Fire Emblem while preserving the deceptive simplicity of Advance Wars. As in FTL, the graphics are 16-bit sprites, and musician Ben Prunty returns to score a swelling-yet-somber soundtrack. But what sets Subset's new game apart is brilliant novelty: You know exactly how and where every enemy is going to attack. This turns the game into a puzzle, since your first priority is to preserve buildings and the people inside them, only obliterating the bug scum when possible.

Subsequently, your toolkit focuses more on shifting the battlefield to your favor, redirecting attacks away from dwindling human infrastructure and, preferably, toward another enemy. Thus, Into The Breach probably won't please folks who just want to clobber giant monsters without consequences. But anyone who likes strategy and isn't afraid to unlearn everything they know about the genre will find the game a refreshing challenge. And just like FTL, it will probably make you rage quit a few times.

"As with FTL, we appreciate it when your choices have consequences, and it's not just a power fantasy entirely on its own. There are obviously elements of the power fantasy [in Into The Breach] in that you are just being a hero in giant mechs, but having a piece of the game requires you to make difficult decisions, and that there are consequences to your decisions, I think makes for interesting gameplay," Matthew Davis, the game's programmer and half of Subset Games, told Engadget. "If it's just a case of you win, win, win, win, win then it gets kind of boring."

Unlike FTL's reliance on randomness, Into The Breach gives players all the information they need to solve every encounter. Like Advance Wars, there are no hit percentages -- you hit what you aim at -- and you can see how much damage an attack will cause before you strike. In practice, this prophetic knowledge is both captivating and weighty, as every mistake is preventable. When an error kills a pilot or ends the whole run, it's all your fault. This is humbling -- I've quit in embarrassment after realizing a dumb move many turns ago doomed my squad -- but there are a few mechanics to ease the sting of failure, like a once-per-battle rewind that lets you start a turn over.

The encounters themselves are small-scale (often eight-by-eight grids) but complex, less like three-dimensional chess than a 3D puzzle where changing one part of the battle shifts others. Occasionally you'll luck out, and a forgotten enemy will get shoved in the way of another's attack; other times, you'll ignore a crucial element, like terrain or a disabling status, and inadvertently cripple your chances. It's a bit like turning over a Rubik's cube to find you misjudged how a sequence of moves would play out, and you feel silly for essentially outsmarting yourself.

When an error kills a pilot or ends the whole run, it's all your fault

But the other big catch-up feature ties in with the game's conceit: If (and when) your mech squad is completely destroyed, you can choose one of your pilots to send back in time, effectively restarting the game. Narratively, all is lost and the bug-like Vex invaders have won, but you can still send one of your skilled heroes into the past to change that new timeline's future, Terminator-style.

Starting a new run with an experienced pilot is a nice leg up (though this advantage is probably more psychological than impactful, Davis said.) But the longer you dwell on this mechanic, the more the game world's grim tone sinks in: A tide of colossal monsters barely restrained by a handful of humans endlessly hurling themselves against the onslaught across infinite timelines.

You'll have to read into the minimal text and flavor for Into The Breach's world to open up, as Subset Games is a firm believer in less-is-more. The studio consists of artist Justin Ma and programmer Matthew Davis, who hammered out the game's concept for nearly two years before bringing on more professionals to help development. Burnt out on space combat after finishing FTL: Advanced Edition, Ma and Davis decided on a tactics game. The pair noticed that movies like Man of Steel and other blockbuster films habitually disregard the human cost of combat carnage. They wanted to create the opposite -- an experience where players labor to save lives as they clash with unyielding threats.

Into The Breach is an intentional rebuttal to FTL in many ways, such as ditching hit-and-evasion percentages for perfect information. And in striving to create the opposite, Ma and Davis explained, they found a way to include even more of the standard rogue-like experience -- the end of one run, the beginning of another -- into the game's overall narrative using the time-travel mechanic. This brings the player completely inside the gameplay loop, enveloping the intermission between play sessions into the narrative.

"So, in FTL, the story is this lone ship on a suicide mission, and succeed or fail, it's try your best... you bash your head against the wall 100 times, and the game story resets each time, and so it's a sort of incompatibility with the player's experience versus what's supposed to be going on in the game," Ma said. "So that's how we came up with the time travel, sending the pilots back, and it's sort of to build the actual game experience into the meta narrative."

By making the strategy game Ma and Davis would want to play themselves, Into The Breach ends up being a response to the genre, too. Not just rejecting annoyances (XCOM's ridiculous miss chance comes to mind) but also chopping out all slow and tedious gameplay. Battles can't be won by attrition, and they shift enough to prevent a single strategy from dominating every encounter. To do this, Subset made most missions last around five turns, streamlining combat to the most exciting moments. Aside from brief introductions from each island's reigning governor, a corporate CEO, there are no cutscenes. This brevity and minimalism reinforces the game's scarcity -- the lack of time, resources and hope.

"That's the reason why each battle is a set time limit rather than until victory," Ma said. "That keeps it short. Knowing that you don't actually have to eliminate all the enemies, you technically just have to survive, and that sort of tone, in itself, really sort of sets up the way we want the player to feel in the entirety of the game."

The idea to give players foresight into enemy plans came when the pair were fiddling with units, and due to some wonky code in an early game build, moving a certain foe shifted its prepared attack accordingly. "We were sort of running on a single enemy being able to show their predicted actions, and then we decided that was fun, so we pushed the whole game in that direction," Ma said.

"Games, to be interesting to us, need to have a stronger core where you can completely ignore all the setting, and absolutely everything, and it still be an interesting game."

What was always central to the game's conceit was straining -- and sacrificing -- to save lives. Enemies alternate between targeting the player's mechs and buildings containing civilians and power. If too many structures go down, you'll lose. The energy grid becomes the campaign's life gauge, and it's prominently displayed up top. But trying to encourage players to save people became a thorny problem -- grant players items or resources for every life, and they'll rescue humans purely for the reward. So the civilian count is just a cosmetic number, a high score to count at the end of your run.

I find that disappointing -- to have labored on this exquisitely balanced strategy system and then pull punches on the moralistic core -- but, as Ma and Davis reminded me, the core isn't the story or the world. It's the thrill of the mechanics playing out in an encounter. "Games, to be interesting to us, need to have a stronger core where you can completely ignore all the setting, and absolutely everything, and it still be an interesting game," Ma said. "We had to balance this whole giving as much theme as possible whilst still letting you play as if there is no theme whatsoever, and it's just a board with pieces."

Into The Breach comes out for Windows today for $15, and then will come the Mac and Linux versions down the line. Subset has no plans to port it to iPad or consoles (including the Switch); they'll revisit that topic after they've seen how the game is received.

Including the time travel mechanic means your mission is never over. When you win, one pilot bravely volunteers to venture to the past anyway to give another timeline a fighting chance. There are infinite worlds to save. Whether you fail or succeed, it's always time to jump, once more, into the breach.

via Engadget RSS Feed "http://ift.tt/2HPRYVq"

Comments

Post a Comment